A Major Malfunction

The Challenger Disaster

Tuesday, January 28, 1986

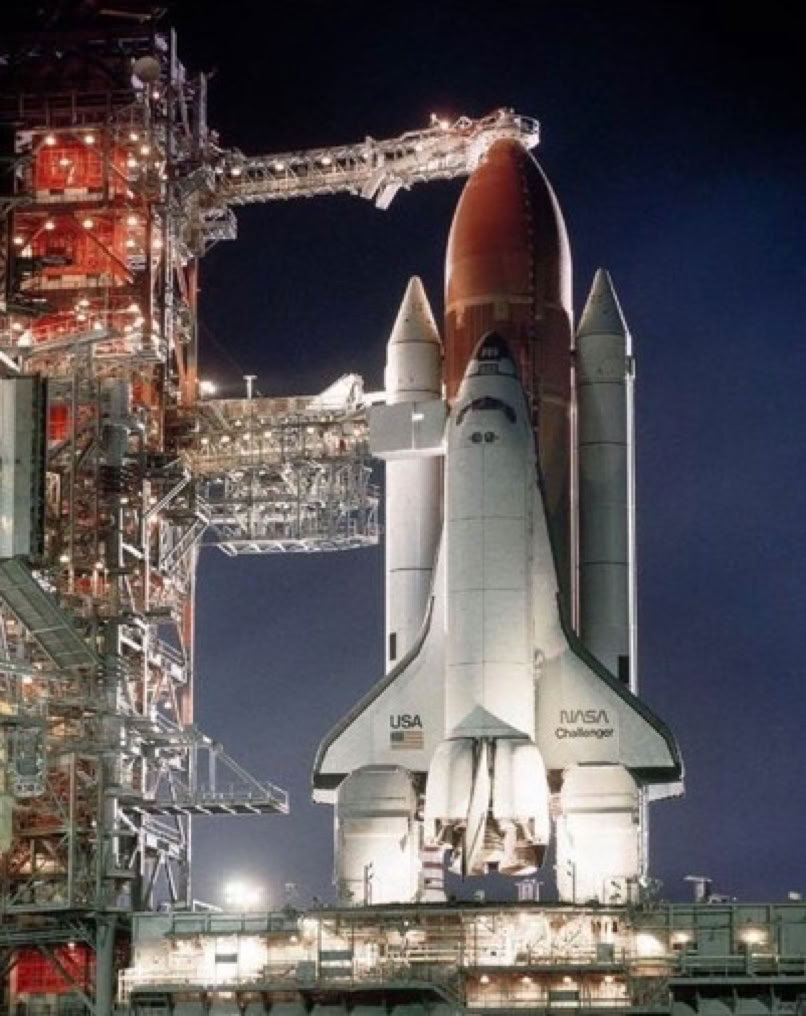

Challenger started out as Structural Test Article STA-099; later converted to space flight it was designated Orbiter Vehicle OV-099. Challenger was lighter than her sister, Columbia, and could carry 1,100kg (1.2 tons) of extra payload. Even with Discovery and Atlantis to share the flights, Challenger flew half of the 20 shuttle missions between her maiden voyage and her last flight: 10 launches, 25.8 million miles, 62 days in space, 995 orbits of Earth, and at least a dozen space firsts:

• First Shuttle spacewalk - Story Musgrave and Donald Peterson, STS-6

• First American female astronaut - Sally Ride, STS-7

• First African-American - Guion “Guy” Bluford, first Shuttle night launch and first Shuttle night landing, STS-8

• First untethered space walk - Bruce McCandless II, STS-41B

• First spacewalk by a woman - Kathy Sullivan, first launch with two women - Ride and Sullivan, first Canadian - Marc Garneau, STS-41G

• First and only post launch abort (abort to orbit, resulting in a lower altitude orbit), STS-51F

• First Dutchman - Wobbo Ockels, STS-61A

• First Shuttle fatalities, STS-51L ...

On Jan 28, 1986, STS-51L suffered a "major malfunction" and broke up shortly after throttle-up, 73 seconds after launch, at 48,000 feet (9 miles), 7 nautical miles downrange and traveling at about 2,100 feet/second (1,450 mph or Mach 1.9).

It was the 25th Shuttle mission and Challenger’s 10th flight in less than 3 years. Challenger was flown more frequently than the other three Shuttles once she was flight worthy in 1983. But the flight schedule was a busy one and Challenger, Columbia, Discovery, and Atlantis were launching frequently with satellite payloads.

There was a lot of pressure at NASA and the 25th Shuttle mission had already been delayed by potentially bad weather at the launch site, bad weather at an abort landing site and on the previous day by a hatch handle bolt that sheared as it was being removed… the battery operated drill used to remove it ran out of power and NASA had no back-up battery for it. By the time the bolt was out, the tanks had had to be emptied and the launch postponed to the next day, when cold temperatures were predicted.

The cold was causing concern with the engineers at Morton Thiokol where the Solid Rocket Boosters were built. Allan McDonald, the Thiokol engineer at the Florida launch, refused to sign the approval for the launch. A telecon between Thiokol and the NASA SRB team was scheduled for the evening of Jan 27...

The catastrophe was caused by O-ring failure in the righthand SRB due to launching at 28F (-2C), when the O-rings would be too rigid to seal as the SRB joints would flex.

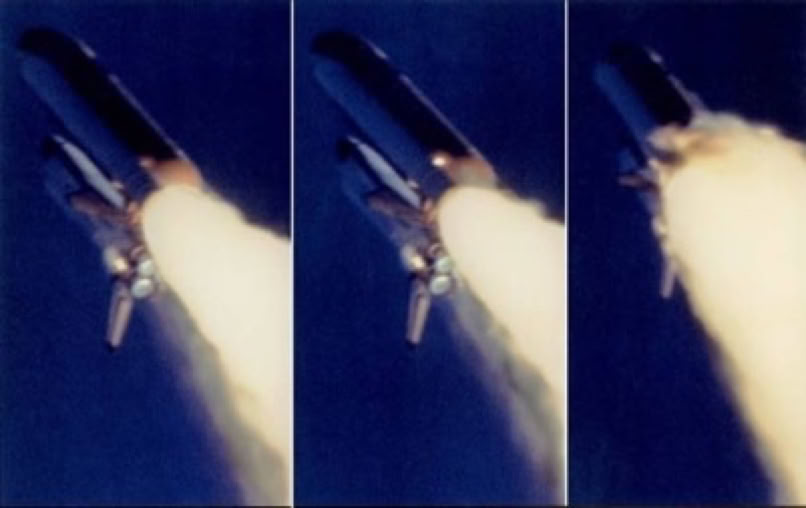

The black smoke plumes seen pulsing for the first three seconds of launch are the result of the o-ring failure. However, it is believed that the gap was quickly sealed by solidified aluminum oxide by-product.

Max-Q is the point in the flight at around 59 seconds into the flight at an altitude of around 35,000 feet where the vehicle experiences maximum aerodynamic pressure (as the Shuttle is moving faster but the air is still not so thin). This caused significant vibration of the stack even with the engines throttled down to 65%. The first evidence of flame on the right SRB aft field joint was seen at 59 seconds.

From 37 seconds the vehicle had been experiencing crosswinds. Just after Max-Q at around 64 seconds, the shuttle is believed to have flown through the jet-stream - it is a rare event for it to be so Southerly, but also connected with the cold weather. The forces of this extreme cross wind caused the boosters to gimble to maintain the correct course. This action flexed the booster structure, dislodging the remaining solids blocking the burnt O-rings. Challenger had run out of luck and the blow-by past the O-rings increased significantly at around 64 seconds.

At this point the engines were throttling back up to 104%. At 68 seconds CAPCOM, astronaut Dick Covey, told Scobee “Challenger, Go at throttle up,” and at 70 seconds Scobee replied “Roger, Go at throttle up.”

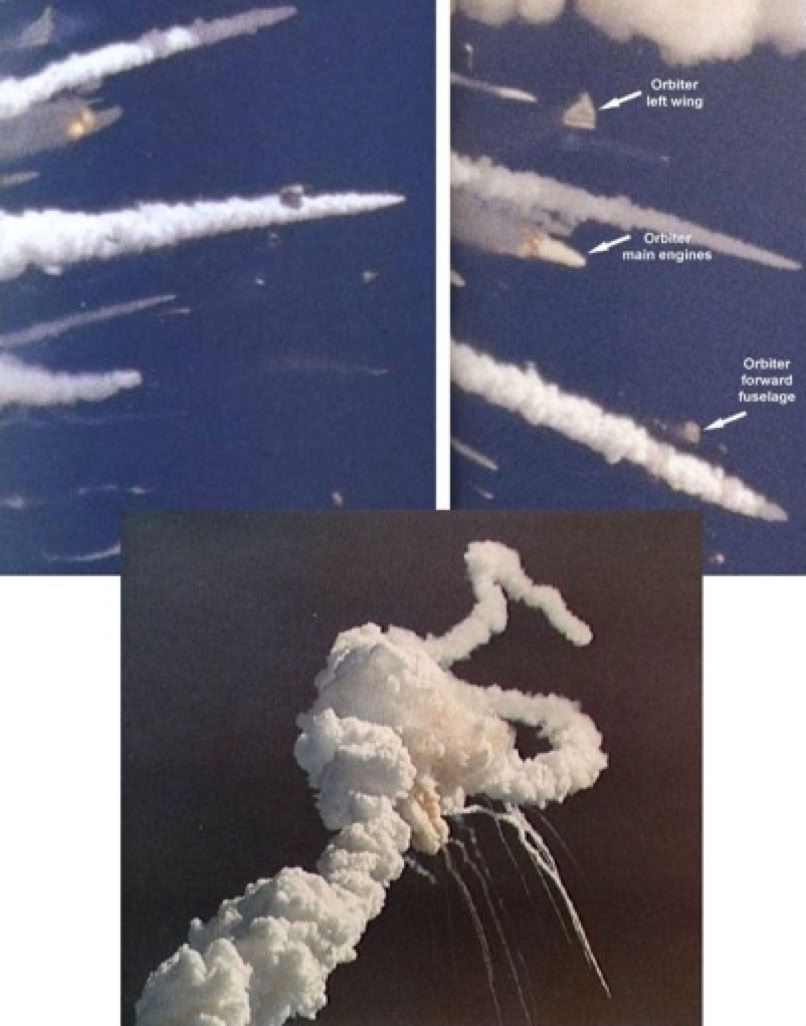

It took about 8 seconds for the blow-by plume to burn through the lower support holding the SRB to the external tank, and once it was loose the SRB rotated. This caused a significant lateral acceleration at 72.5 seconds. On a tape from a ‘black box recorder’ recovered weeks later, Mike Smith was heard to say “Uh, oh” at 73 seconds. The loose SRB then rotated back and ruptured the ET causing uncontrolled burning of the liquid hydrogen and oxygen and consequently, in a matter of milliseconds, the disintegration of the ET that holds the stack together at 73.2 seconds. This was immediately followed by 100 milliseconds of interference on the downlink, the subsequent break-up of the orbiter and complete loss of signal 74.1 seconds after launch.

Artist John Berkey’s impression could well be very accurate.

The forces of the break-up at around 12G were survivable and no more than an ejection seat in a fighter jet, and only brief - for a couple of seconds; it is unlikely that the crew were badly injured. After 10 seconds the crew cabin (or forward fuselage) was essentially in a 'free fall' trajectory. The slowly tumbling, intact crew cabin was photographed missing its nose cone at the front, and trailing cables from the rear. It had a peak trajectory of 65,000 feet (12 miles) 25 seconds later and stabilized in a nose-down attitude caused by the drag of the trailing cable harness. After a further two minutes and twenty seconds the crew module hit the Atlantic ocean about 16 miles or so east of the launch pad.

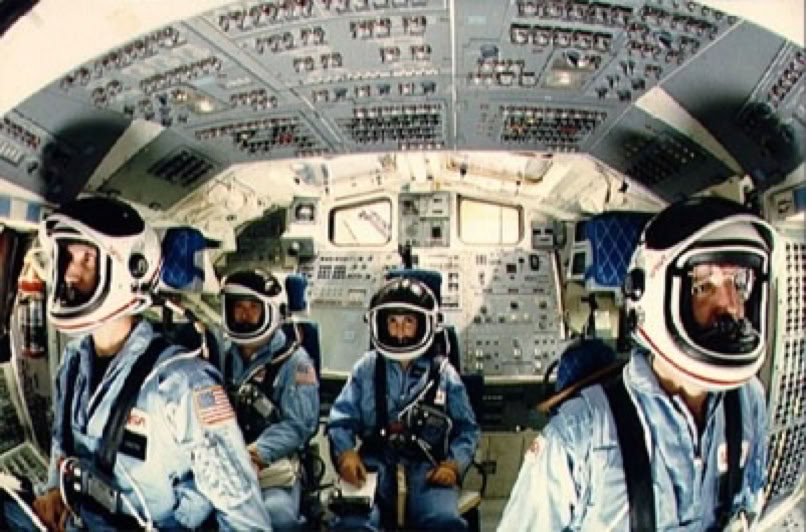

At least some of the crew were conscious after Challenger broke up, evidenced by manual activation of 3 of the 4 recovered personal egress air packs, and by pilot Mike Smith having activated several switches. Ellison Onizuka, seated behind the pilot, activated Mike Smith's PEAP. Commander Dick Scobee's PEAP was not activated - it is unlikely that Judy Resnik could reach it while strapped in.

It is doubtful that the cabin depressurized, or it did so slowly, and consequently the crew are likely to have been conscious until the left-hand forward corner (near Dick Scobee's seat) hit the water at about 200mph, whereupon the crew cabin broke apart under forces of about 200G and the crew died instantly, still strapped into their seats. If the cabin had landed gently, they could have swam home.

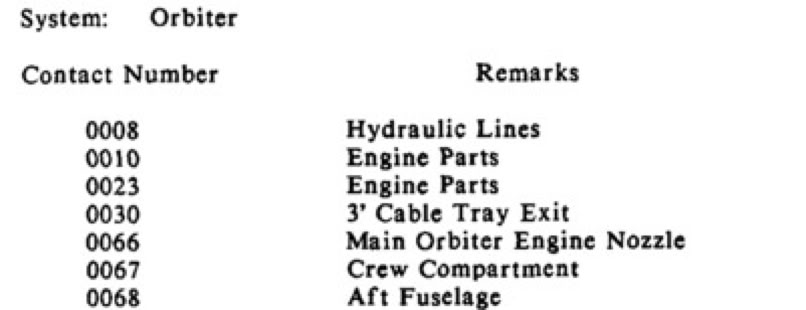

During the recovery search, the crew cabin (known as ‘Object D’ on radio transmissions) was identified as sonar contact 0067.

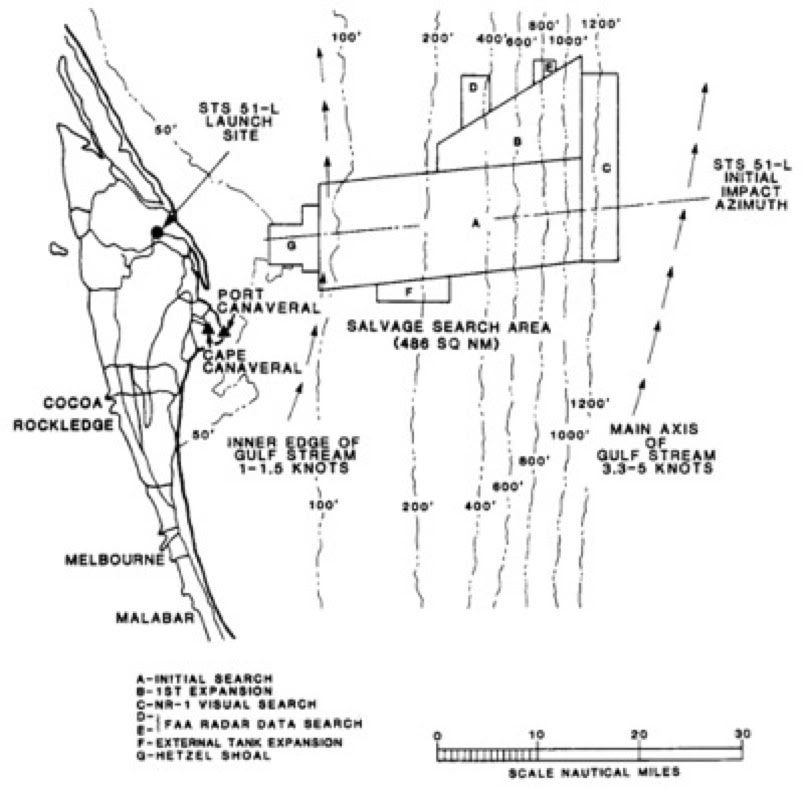

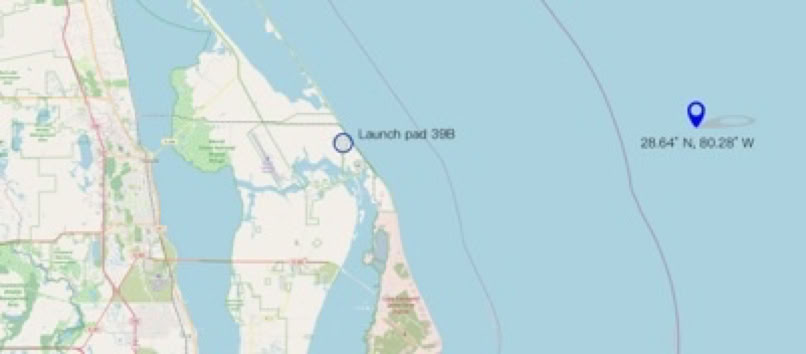

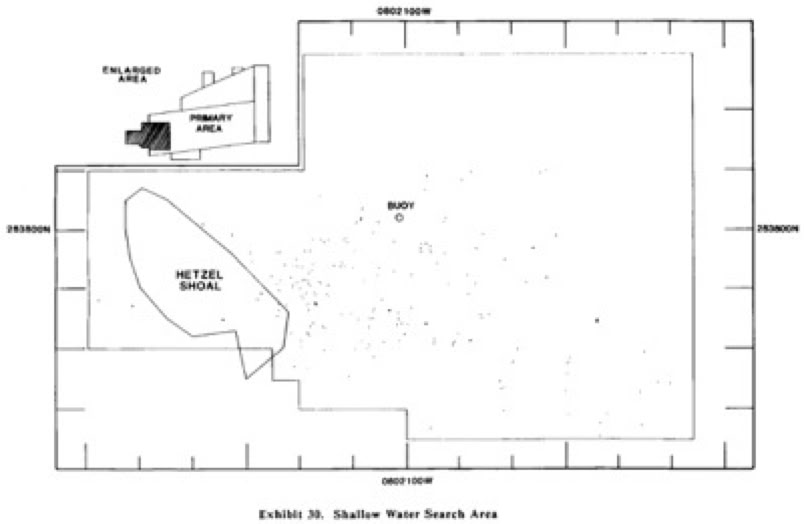

During the search the site was known as "Target 67" within a debris field about 5 miles by 7 miles around Hetzel Shoal within the area labeled G on the salvage map, about 16 miles east of the pad at 28.64° north, 80.28° west.

The crew cabin was formally identified on March 8th and US Navy divers on the USS Preserver completed recovery of the debris by April 4th. Six of the crew were recovered almost 6 weeks after the accident from a depth of 100 feet below the surface of the Atlantic.

The last crew member, Greg Jarvis, floated away and was lost to divers as they attempted his recovery, but found a month later some 0.7 nautical miles from the crew cabin. Greg Jarvis had been bumped from two previous flights, from April 1985 and earlier in Jan 1986 to make room for members of congress to fly; Sen. Jake Garn (R-Utah) and Rep. Bill Nelson (D-Fla).

The crew cabin showed no signs of burn damage; only damage from impact with the water.

Other parts of the orbiter and SRBs were found during the recovery. And some washed up on the shore much later.

NASA issued a statement that the crew had died instantly, vaporized by the explosion. They even issued death certificates on Jan 30, which was legally inappropriate before the crew remains were found. They stuck to their story. They kept the crew remains under armed guard and denied the medical examiner the opportunity to perform autopsies and issue real death certificates, which were his legal duties. NASA wanted to maintain the idea that nobody suffered at any cost (presumably to soften the PR nightmare of having killed 7 people through dereliction of management duties) just like they had for the Apollo 1 fire after which Betty Grissom had to sue NASA to find out what really happened to her husband.

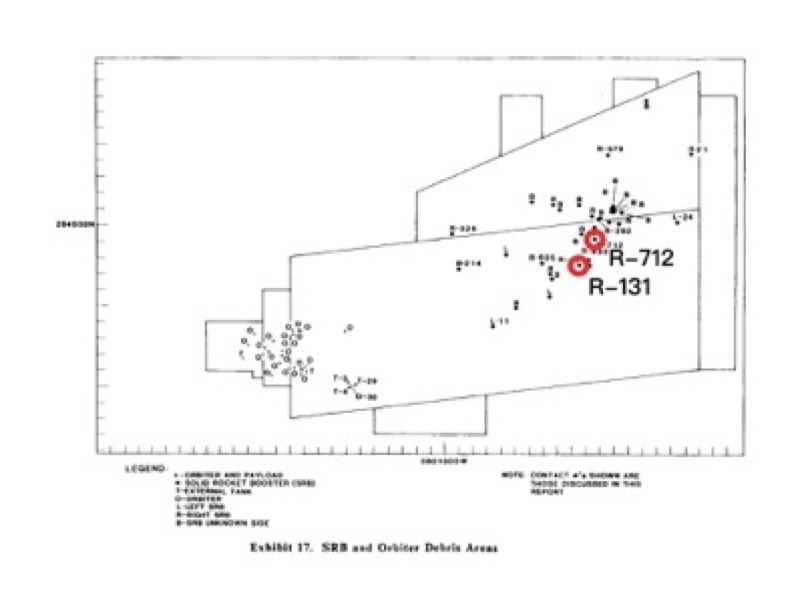

During April the critical pieces of the aft joint of the right SRB were located by sonar (sonar contacts 131 and 712) 35 miles from the launchpad, at a depth of 560 feet, and recovered.

They revealed a hole about 28" wide with soot-blistered paint around its edge, proving the burn-through theory. The O-ring failed on the SRB at a point only two feet from the ET and the SRB support. Had it occurred at a point facing outward, away from the ET, the disintegration of the stack may not have happened, but the SRB would have had to burn for at least another 50 seconds before SRB separation.

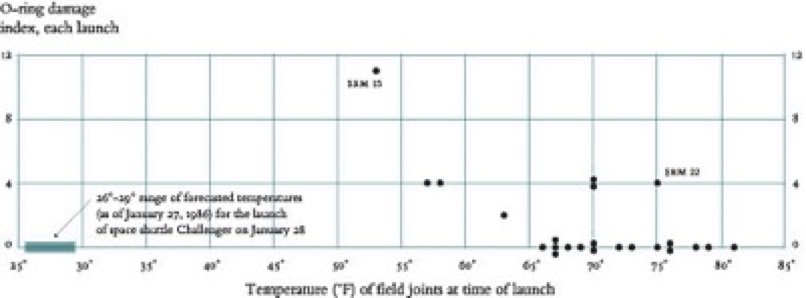

There were no data for launch below 54F (+12C) and the O-ring 'redline' was supposedly 39F (+4C). The temperature of the SRB at launch was about 28F (-2C).

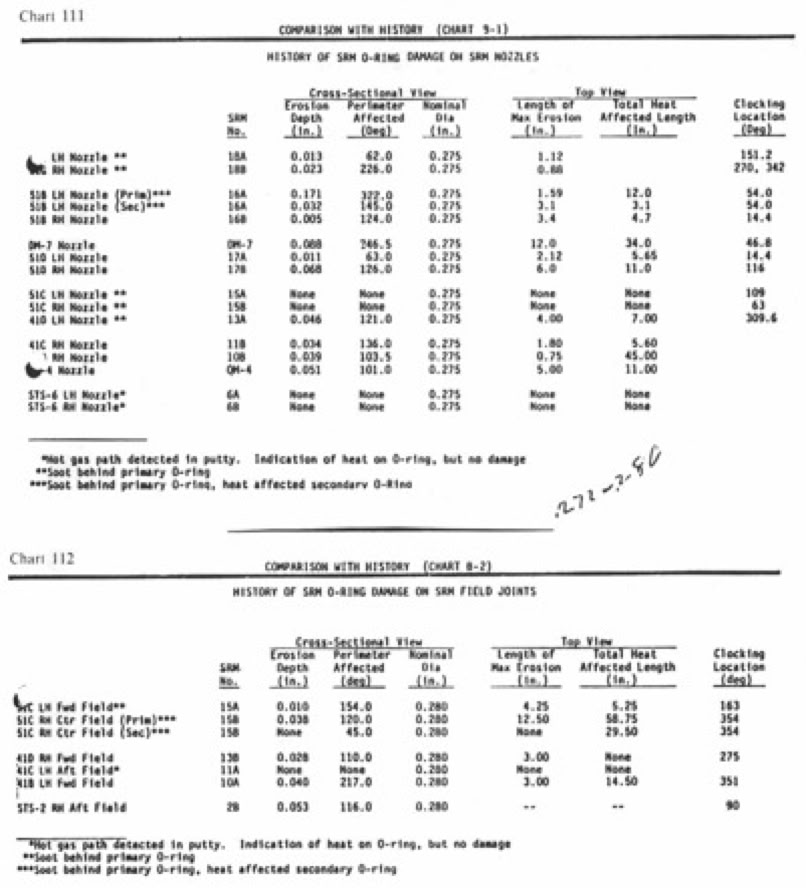

STS 51-C had launched in Jan a year earlier, at around 54F. One O-ring had burned through, and the second O-ring was damaged but had held. In their report of Feb 1985 Thiokol engineers expressed for the first time a significant concern with O-ring function and low temperatures. It’s not actually rocket science to see the risk increase if you extrapolate from the STS 51-C data:

The warnings from Morton Thiokol engineers Roger Boisjoly and Bob Ebeling about temperature and O-ring failure and the recommendation to wait for warmer temperatures of at least 53F did not go down well with NASA; "My God, Thiokol," responded Lawrence Mulloy of NASA's Marshall Spaceflight Center, and NASA project manager of the SRB program, "when do you want me to launch? Next April?" NASA's own policy stated that failure of Criticality 1 components cannot be relied on with only one back-up system (especially when the secondary O-ring was similarly out of specification at that low temperature), and in spite of the Thiokol engineers unanimous recommendation, NASA's SRB project leaders persuaded Thiokol management to reverse their no-go (without informing other NASA bosses - another breach of NASA protocol).

Bob Ebeling went on to help restore the 65,000-acre Bear River migratory bird refuge in Utah, and Roger Boisjoly used the Challenger disaster as an example in his lectures on leadership and workplace ethics.

Roger Boisjoly was given the Award for Scientific Freedom and Responsibility by the American Association for the Advancement of Science "For his exemplary and repeated efforts to fulfill his professional responsibilities as an engineer by alerting others to life-threatening design problems of the Challenger space shuttle and for steadfastly recommending against the tragic launch of January 1986."

The disaster was investigated by the Rogers Commission, made up of several senior and high profile individuals. The famous physicist Richard Feynman was part of the Rogers Commission along with astronauts Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride.

In a closed hearing Lawrence Mulloy testified that there had been no proof that the cold temperature was unsafe. He simply said that Thiokol had some concerns but approved the launch. In his testimony that had a loose affiliation with the truth, he neglected to say that the approval came only after Thiokol executives, under intense pressure from NASA officials, overruled the engineers.

"I was sitting there thinking that's about as deceiving as anything I ever heard," McDonald recalled. He was not supposed to speak, but he was courageous, stood up, and interrupted proceedings. "So... I said I think this presidential commission should know that Morton Thiokol was so concerned, we recommended not launching below 53 degrees Fahrenheit. And we put that in writing and sent that to NASA."

It quickly became apparent that NASA and Morton Thiokol were not being transparent about the O-ring problem. Astronaut Sally Ride was given data from Morton Thiokol about the performance of, and damage to O-rings in launches at cool temperatures. She risked her career and gave this piece of paper to Major General Kutyna, whom she knew could pass it to Richard Feynman. Kutyna kept this secret until Ride died in 2012.

After he saw the O-ring temperature data, Feynman had to figure out how to make this known without revealing the leak, so he performed a very simple experiment with some iced water that blew open the idea that there was no evidence the O-rings were unsafe at cold temperatures.

Feynman was very critical of NASA management and insisted that his findings on the matter be included in the Rogers report.

In Appendix F of the report from October 1986 Feynman stated:

“It appears that there are enormous differences of opinion as to the probability of a failure with loss of vehicle and of human life. The estimates range from roughly 1 in 100 to 1 in 100,000. The higher figures come from the working engineers, and the very low figures from management. What are the causes and consequences of this lack of agreement? Since 1 part in 100,000 would imply that one could put a Shuttle up each day for 300years expecting to lose only one, we could properly ask ‘What is the cause of management's fantastic faith in the machinery?’... It would appear that, for whatever purpose, be it for internal or external consumption, the management of NASA exaggerates the reliability of its product, to the point of fantasy.”

Feynman added "For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled."

Many of the engineers at Morton Thiokol were devastated by the tragedy and never outlived their feelings of guilt. Lawrence Mulloy never felt any guilt and maintained that he would make the same decision to launch.

It was 21 months before the next Shuttle launch, and astronaut Dick Covey who had been CAPCOM when Challenger exploded was Discovery’s pilot.

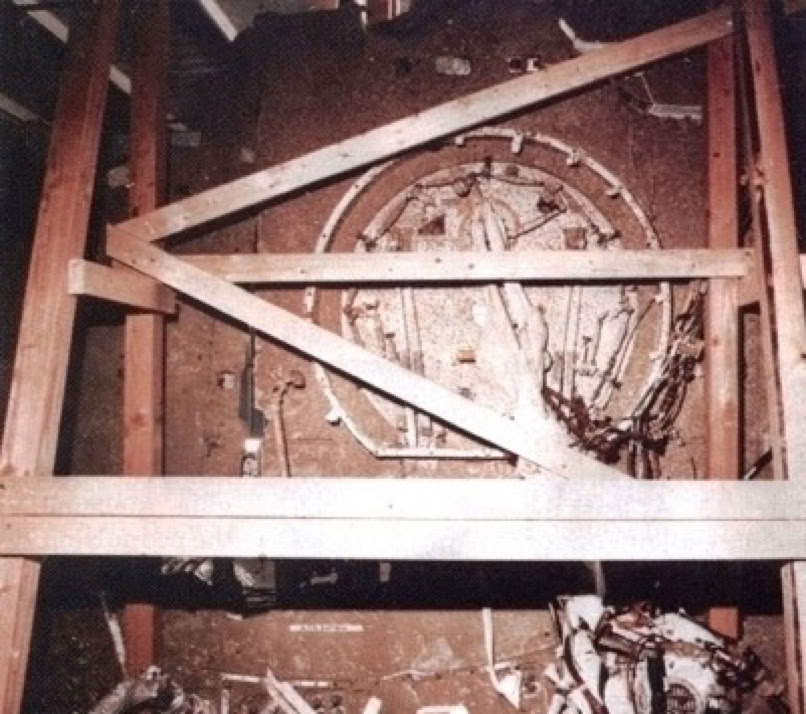

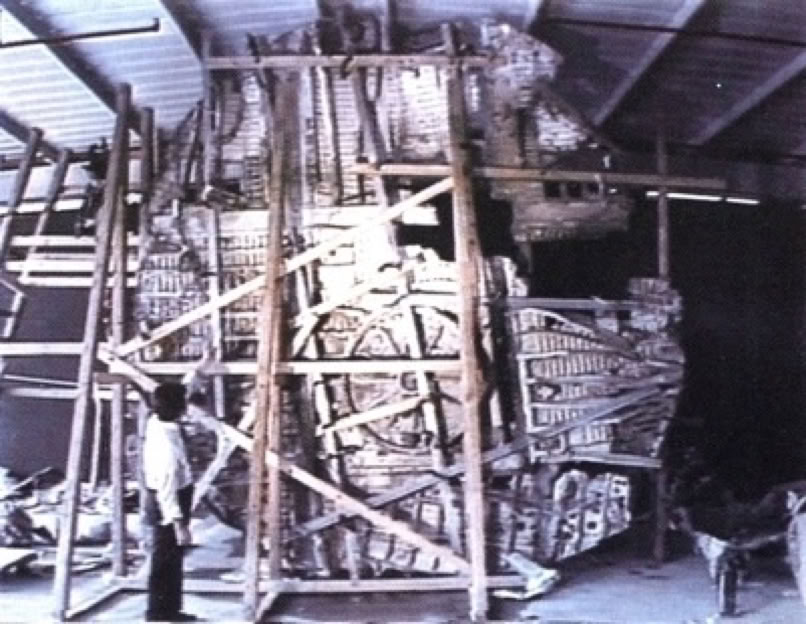

In all, only about 45% of the wreckage was recovered. Without fuel, the Shuttle stack weighed almost 280 tons, and no more than 118 tons of debris was found.

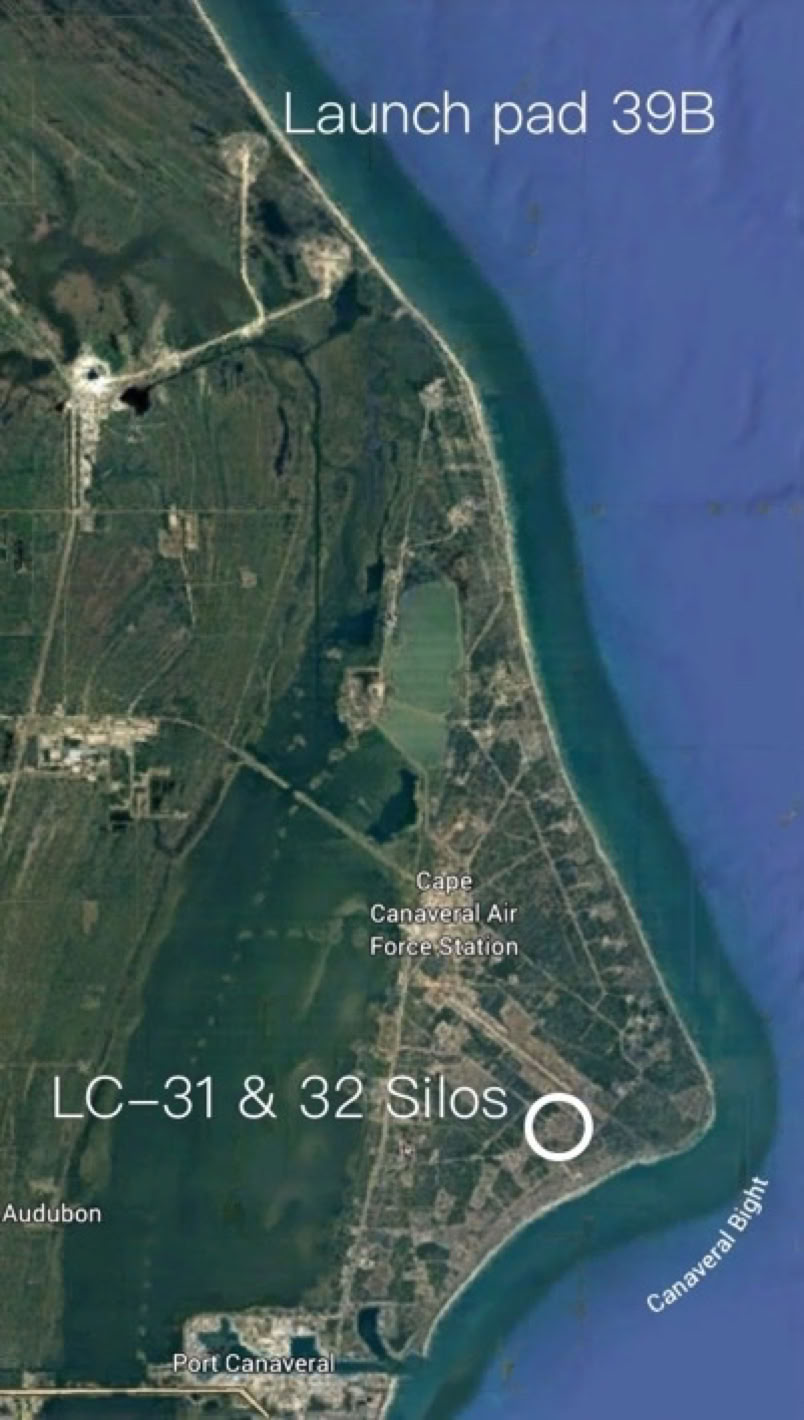

In January 1987, almost a year after the disaster, all of the recovered debris was transferred to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, about about 2 miles south of the launch site. There the debris was placed in two disused Minuteman missile silos, LC-31 and LC-32, each 12’ in diameter and 90’ deep.

Some of the larger pieces were cut up to fit, including the right wing and larger sections of the external tank. Over the next few weeks 102 crates were stored and each silo capped with a 10,000 lb concrete slab.

One of the left wing elevons (wing flap) measuring about 6’ by 15’ washed up at Cocoa Beach 15 miles south of the launch site in December 1996. This was also placed in one of the silos.

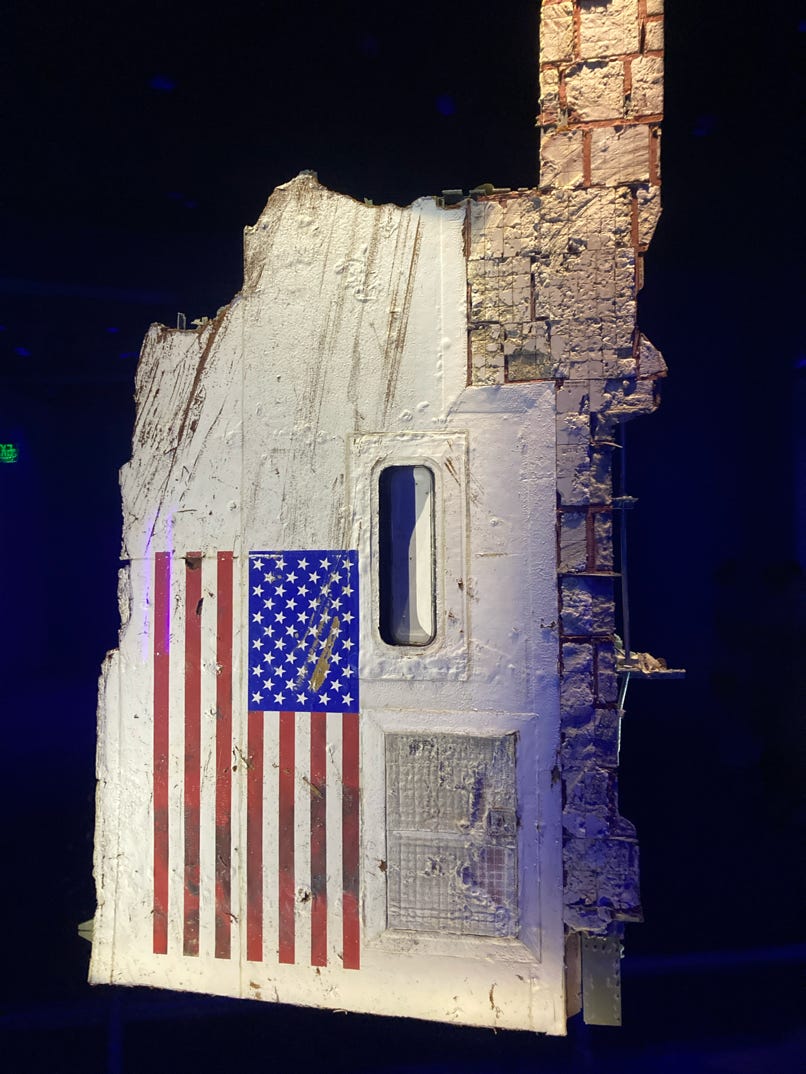

The section from Challenger’s left side bearing the Star-Spangled Banner was removed from the silo and put on display in 2015 as a memorial at the Kennedy Space Center.

From left to right: Christa McAuliffe, Greg Jarvis, Judy Resnik, CDR Dick Scobee, Ron McNair, PLT Mike Smith, and Ellison Onizuka